Young caregivers: handing over their lives to long-term care before they have a chance to grow up.

The first bus at 5 o’clock in the morning is always empty. A fifth-grade elementary school student, A-Tai (pseudonym), got on the bus in front of the hospital. He had just woken up in his mother’s hospital room and had to rush back to his home in Shihgang, Taichung, which takes an hour by bus, change into his uniform, and go to school.

A-Tai is the only family member of his mother, and also her caregiver, even though he is still a minor.

When his mother was hospitalized, the hospital became Ah Tai’s home. While his classmates did their homework at home, Ah Tai put his aside to accompany his mother, listening to the doctor’s advice and giving her water and medicine. During his free time, Ah Tai would connect to the hospital’s Wi-Fi and retreat into the world of mobile games. According to Zheng Ya-wen, a social worker from the Home-Family Foundation, Ah Tai’s mother suffers from lupus erythematosus, is almost blind in one eye, and has had both breasts removed due to malignant tumors. She worries that she won’t live much longer and reminds her son from time to time: “I won’t be around much longer. When the time comes, let the social services department arrange for you to live in an institution.”

The fear of “losing his mother” makes A-tai bite his nails and clothes anxiously every day, and he has bitten several holes in his collar.

At an age when he should be focusing on his studies and laying the foundation for his future, A-tai is already carrying the burden of losing a loved one and the anxiety of being a caregiver. Academic achievement is no longer the most important thing on his list of priorities. This is the portrait of a “young caregiver”.

Among the young caregivers interviewed in the “Vision Project”, A-tai is not the youngest. Some children as young as five years old have started to share household chores and help their physically disabled fathers with tasks such as washing their backs, while others have been changing their paralyzed mother’s diapers since the age of seven.

The alternation between “academic studies” and “caregiving” makes up the day and night of young caregivers. If the younger generation gradually moves towards the role of “caregiver” and deviates from school education, what kind of impact and loss will they face in their future?

Many countries are actively intervening, while Taiwan is unaware and still using filial piety as a justification.

“Those who look at the long-term picture realize that young caregivers are sacrificing their future lives.” said Guo Ci-An, chairman of the Family Caregiver Association. Students who drop out or delay employment to provide care may have difficulty finding their ideal job in the future.

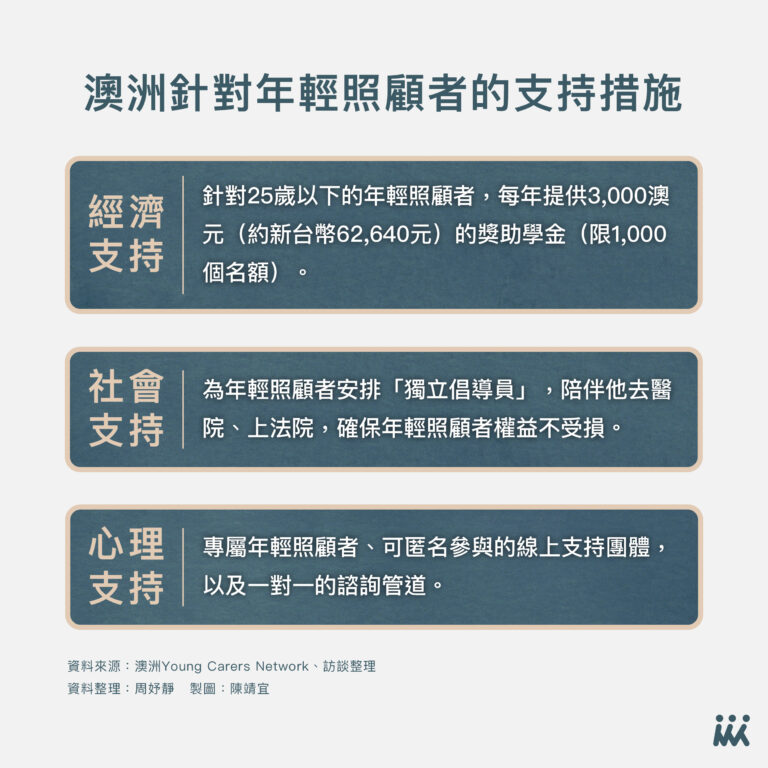

“The Australian government sees this as a national security issue,” Guo said. The difficulty for young people in finding employment affects the productivity and competitiveness of the country, and the government still needs to take responsibility when they cannot ensure their own livelihood.

The issue of “young caregivers” has emerged in various countries. Far-sighted countries have seen the presence of young caregivers and proposed solutions. The Australian Ministry of Education has established a referral process for young caregivers: schools identify students who are caring for family members, first arrange for psychological counseling for students, and then connect students to long-term care resources. “The Australian government has vowed to ensure that young caregivers can graduate from high school without dropping out,” Guo said.

Not only Australia, but the UK and Japan have also conducted nationwide studies. Nottingham University in the UK estimates that up to 20% of students are taking on caring responsibilities. To protect the rights of young carers under the age of 18, the UK government dispatches social workers to assess their care abilities and willingness, understand their career plans, and connect them with resources to avoid young carers sacrificing their own future for long-term care. The Japanese government’s survey shows that there is an average of one young carer per class in primary and secondary schools, with 10% of students spending an average of seven hours a day caring for family members. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Ministry of Education established the “Support Group for the Welfare, Nursing, Medical Care, and Education of Young Carers” to work together to identify young carers as early as possible and ensure that their career development is not restricted by long-term care.

In contrast, the Taiwanese government has no sense of crisis about the plight of young carers. Not only is there no investigation into the basic numbers and strategies, but the “National Filial Piety Awards” continue to be held, praising the care of underage children for their family members. The more pitiful their situation, the easier it is to win awards, highlighting “filial piety.”

Looking at the deeds of the filial piety award winners reported by the media, a seven-year-old grandson took care of his 80-year-old blind grandmother alone; a 13-year-old girl took care of her sick mother, brother with severed fingers, and elderly grandmother alone, winning the award for doing four people’s work alone. Some winners have to work part-time while studying to support their families in caring for their sick relatives.

“This is very embarrassing for advanced countries,” emphasized Chen Jing-ning, secretary-general of the Association of Family Caregivers and Caregiving. Children and minors are the objects that need to be taken care of by adults and the government. The government should review why children have to sacrifice their right to education, right to play, and all kinds of “childish” responsibilities to take care of their relatives.

What the country should do is not to “give awards to encourage children to suffer” but to think about how to intervene and allow them to grow well. Chen Jing-ning pointed out that “when children encounter difficulties, if someone accompanies them, maybe their future life won’t be so difficult.”

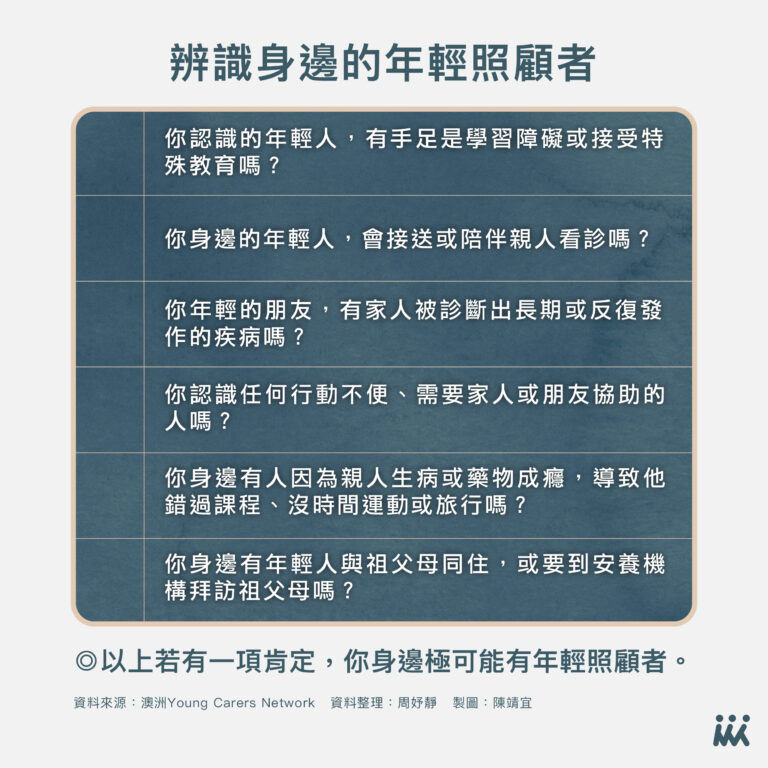

Schools are the first line of defense in identifying young caregivers.

In situations where adults lack awareness and children don’t actively seek help, young caregivers become an invisible issue. “How do we find these people? And how do we help them?” Huang En-hui worries for other young caregivers: “They need more companionship,” anxiously thinking about possibly losing family members and being overwhelmed, “how can they focus on their studies?” “Frontline workers need to raise their sensitivity and recognize that this is a new issue,” Chen Jing-ning said. With the aging population and low birth rates, there will be more and more young caregivers. She believes that the Ministry of Education should first establish a reporting system for schools, so that teachers are aware that young caregivers need assistance. Most importantly, the country should give young caregivers the option to choose – if there is a choice, they do not have to give up their own lives for long-term care.

Seeing the figure of young caregivers, entering their overly heavy childhood, please see the full report here.